The goals of fluid resuscitation include:

- improving central and peripheral circulation – i.e. decreasing tachycardia, improving BP and pulse volume, warm and pink extremities, a capillary refill time < 2 seconds

- improving end-organ perfusion – i.e. achieving a stable conscious level (more alert or less restless)

- urine output ≥ 0.5 ml/kg/hour or decreasing metabolic acidosis.

Treatment of shock

Compensated shock:

- DSS is hypovolemic shock caused by plasma leakage and characterized by increased systemic vascular resistance, manifested by narrowed pulse pressure (systolic pressure is maintained with increased diastolic pressure, e.g. 100/90 mmHg).

- When hypotension is present, one should suspect that severe bleeding, and often concealed gastrointestinal bleeding, may have occurred in addition to the plasma leakage.

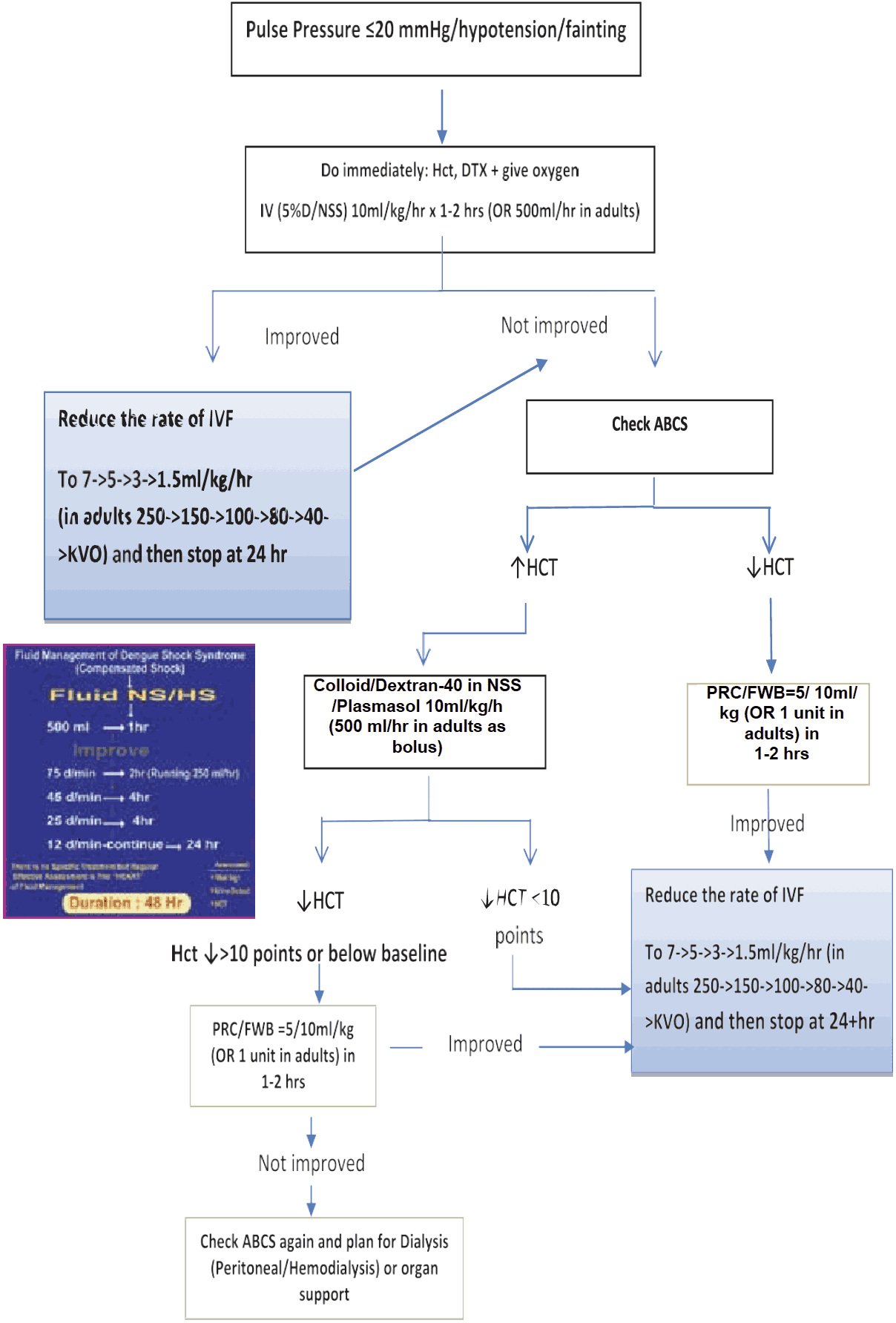

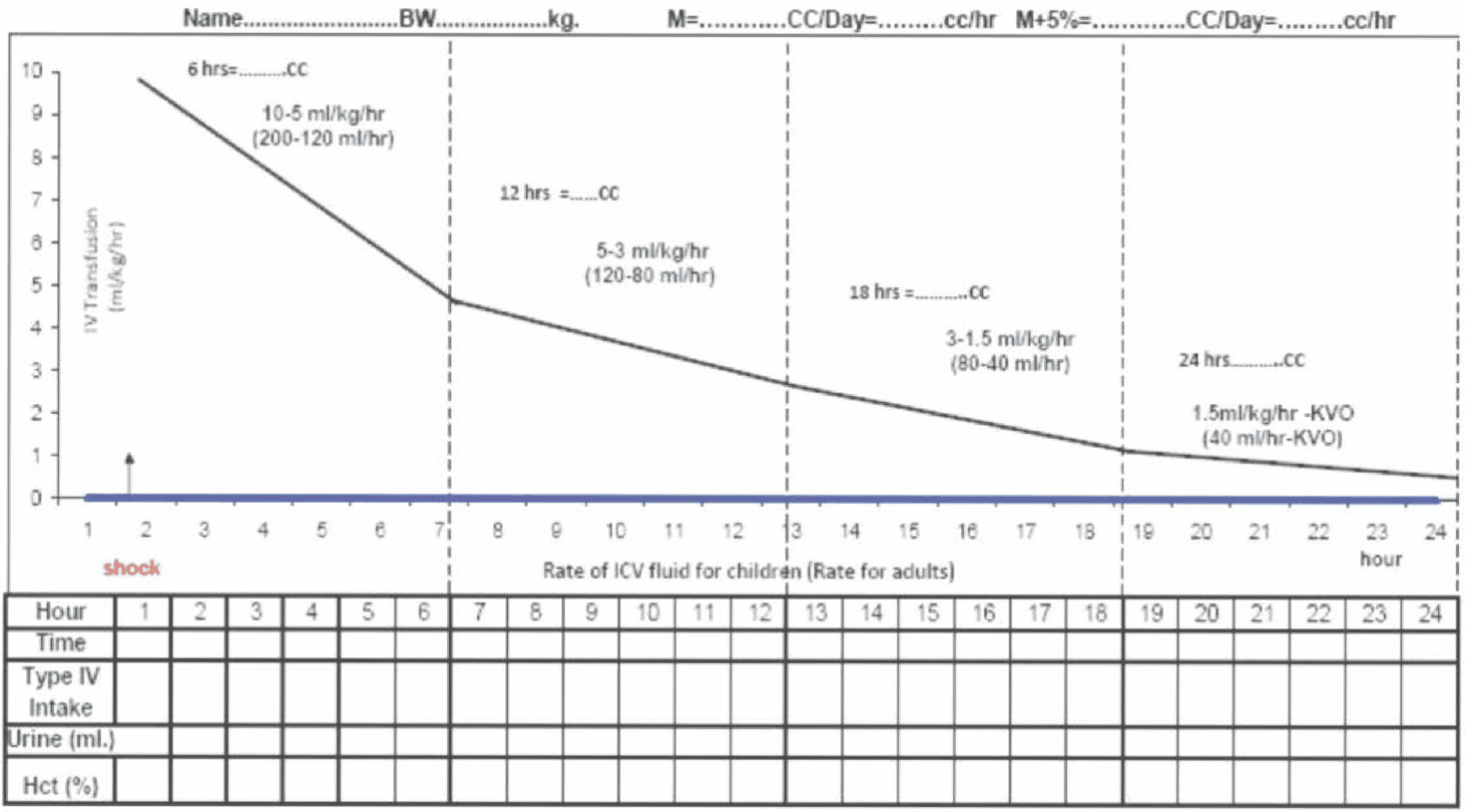

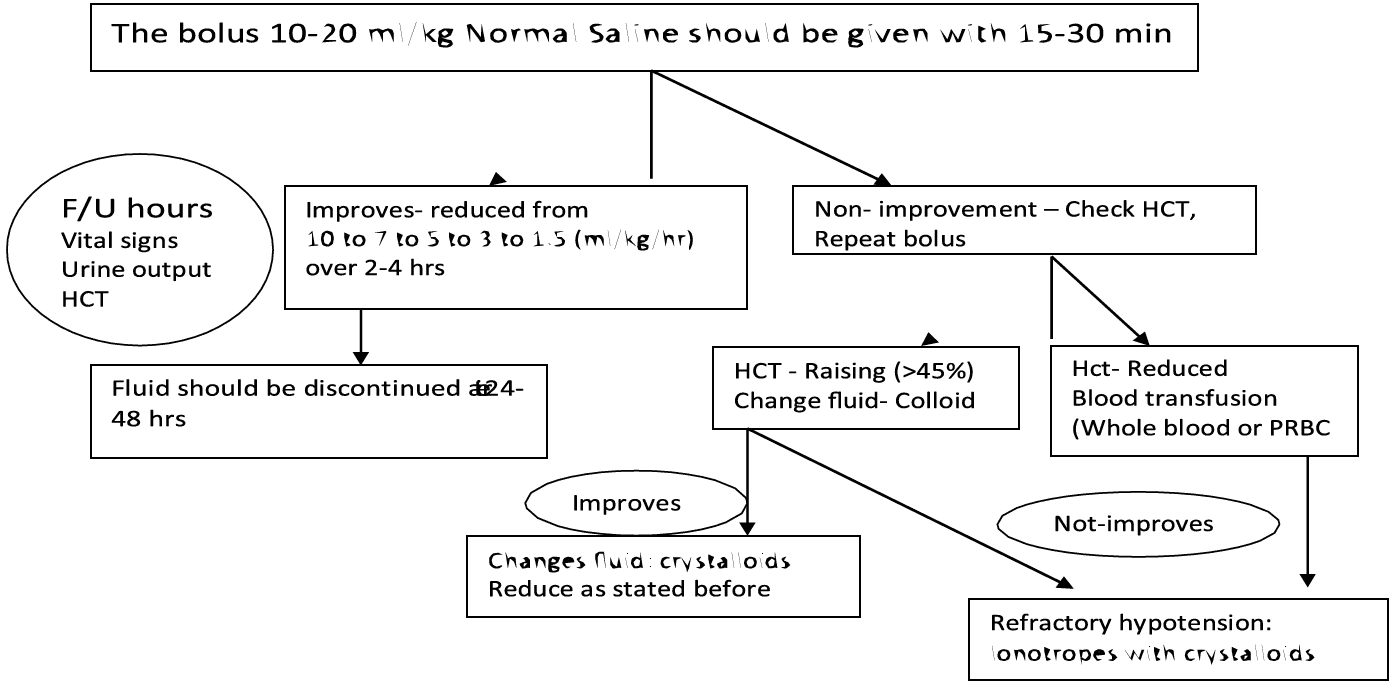

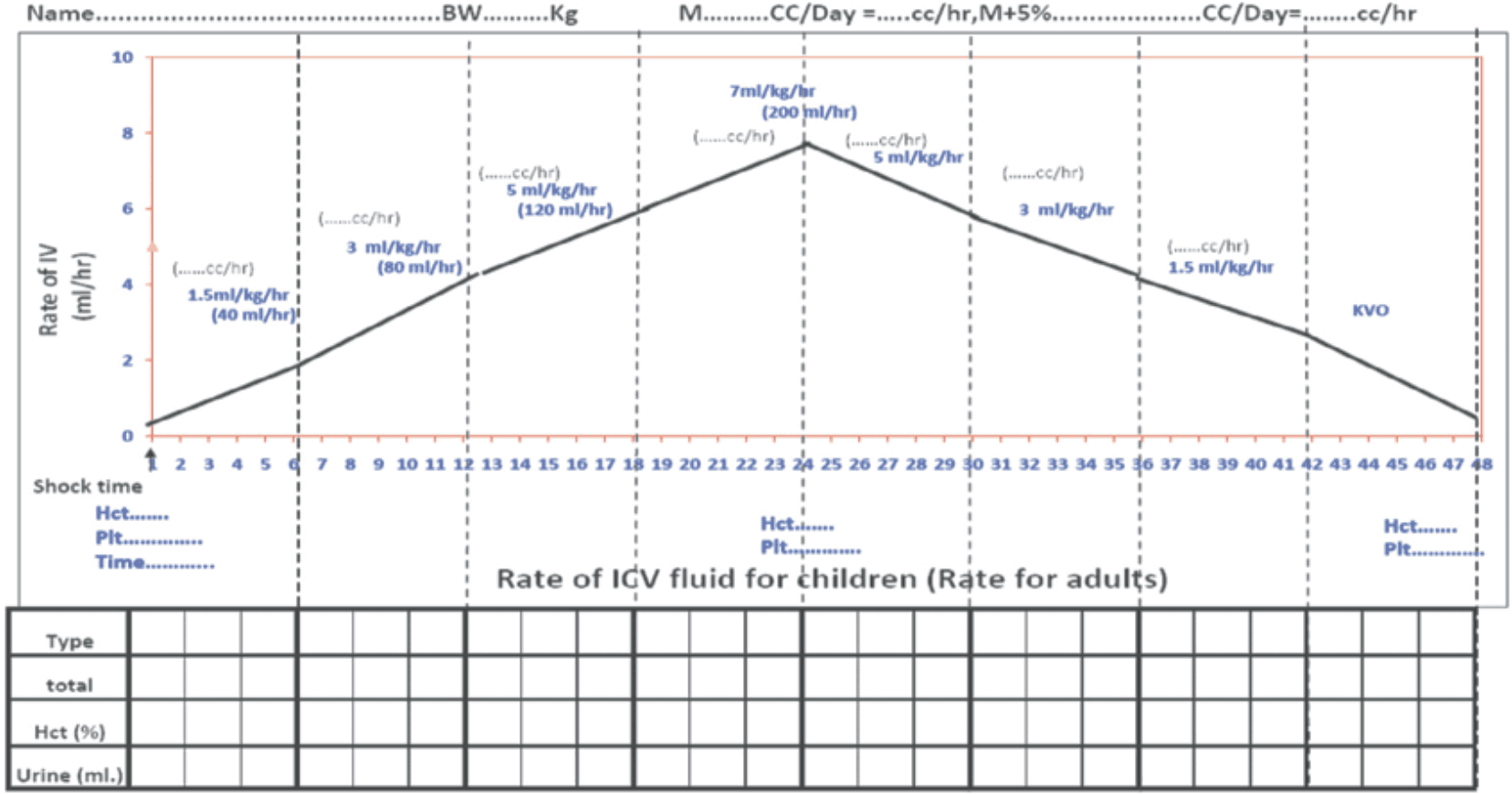

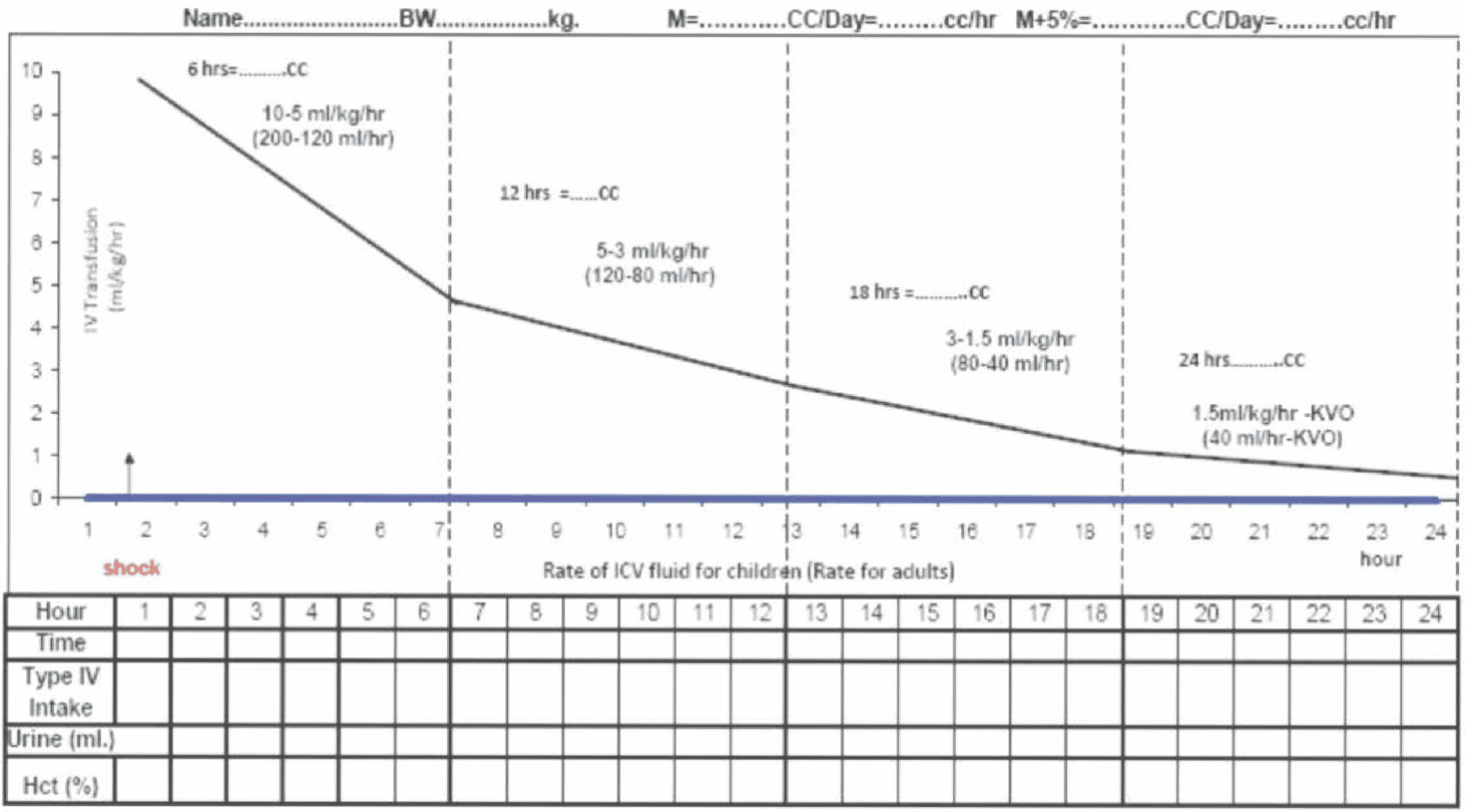

- Most cases of DSS will respond to 10 ml/kg in children or 300–500 ml in adults over one hour or by bolus if necessary further, fluid administration should follow the graph as in Figure 12.

- However, before reducing the rate of IV replacement, the clinical condition, vital signs, urine output and haematocrit levels should be checked to ensure clinical improvement.

- It is essential that the rate of IV fluid be reduced as peripheral perfusion improves; but it must be continued for a minimum duration of 24 hours and discontinued by 36 to 48 hours.

- Excessive fluids will cause massive effusions due to the increased capillary permeability. The volume replacement flow for patients with DSS is illustrated below.

Figure 12 - IV FLUID THERAY for Compensated Shock

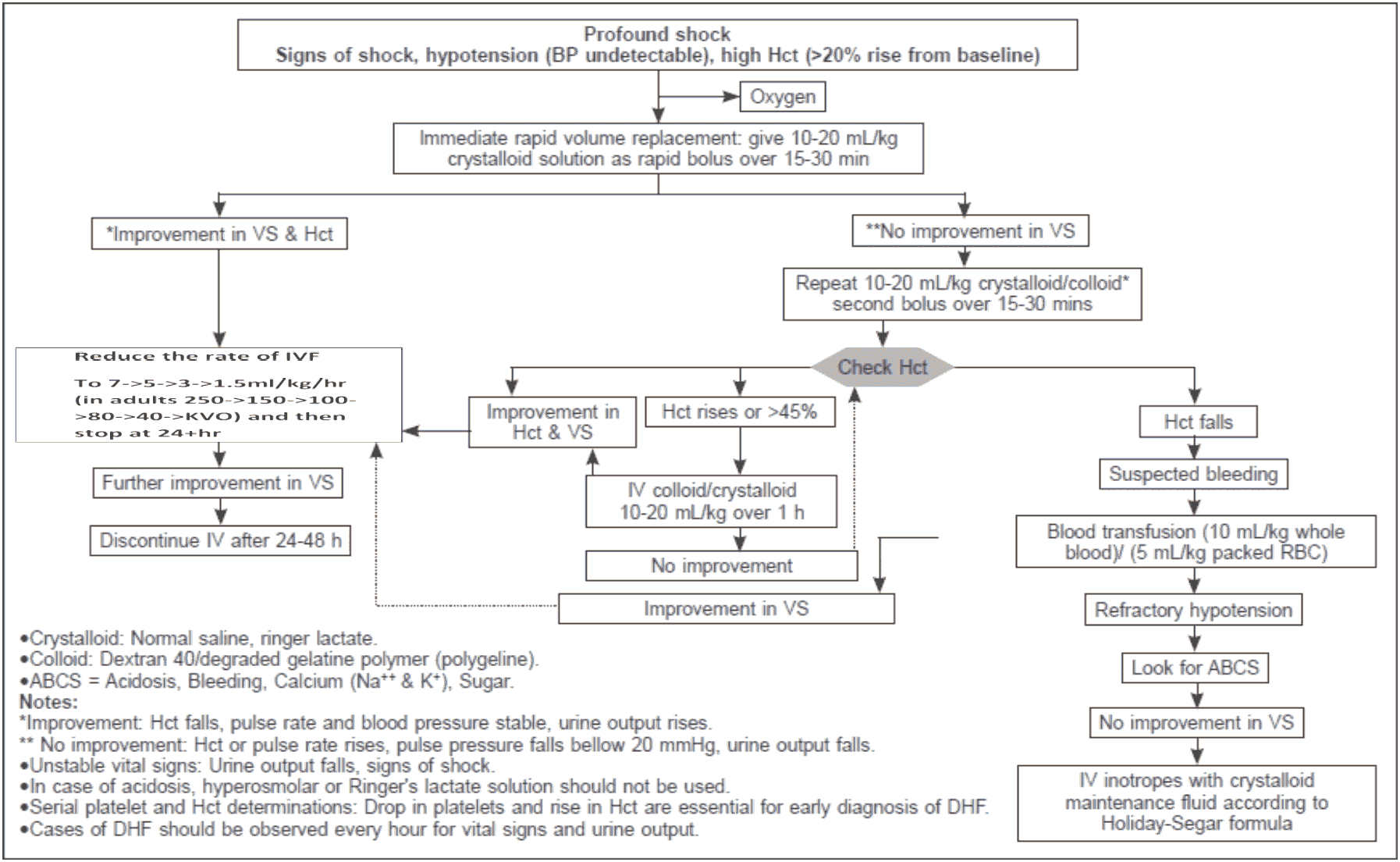

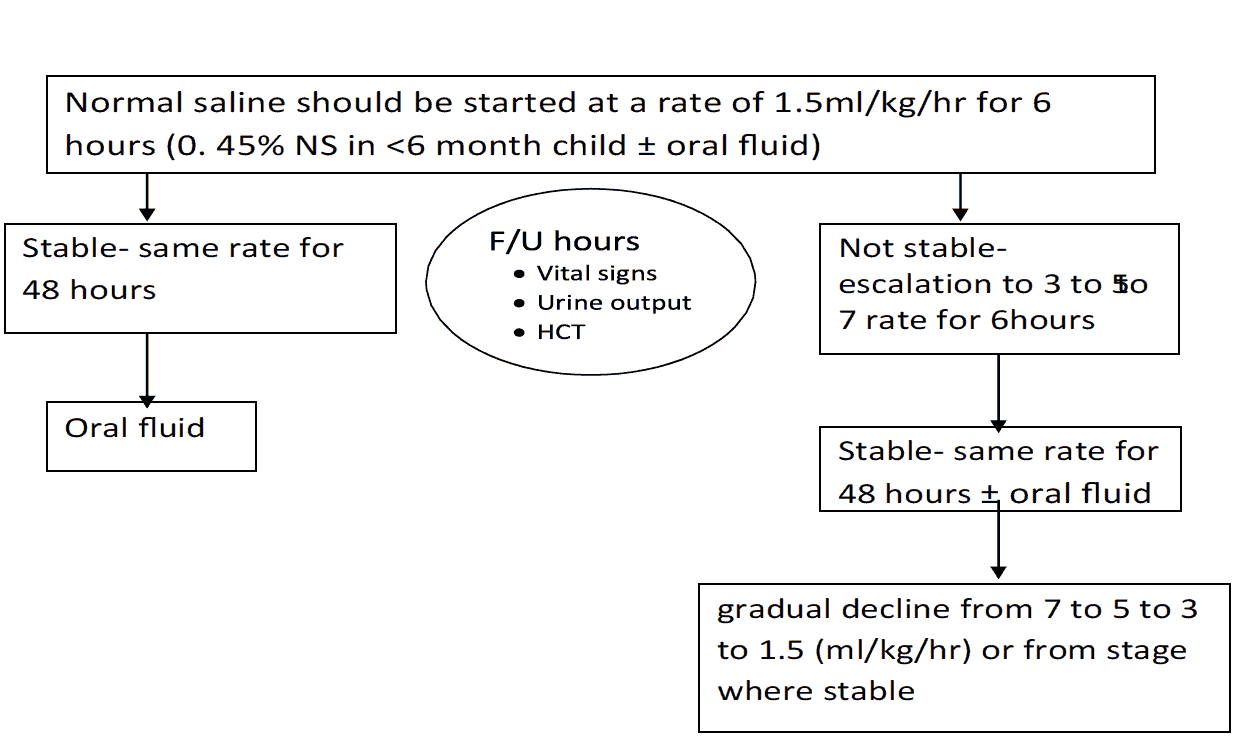

IV Ddjust on shock grade III, IV

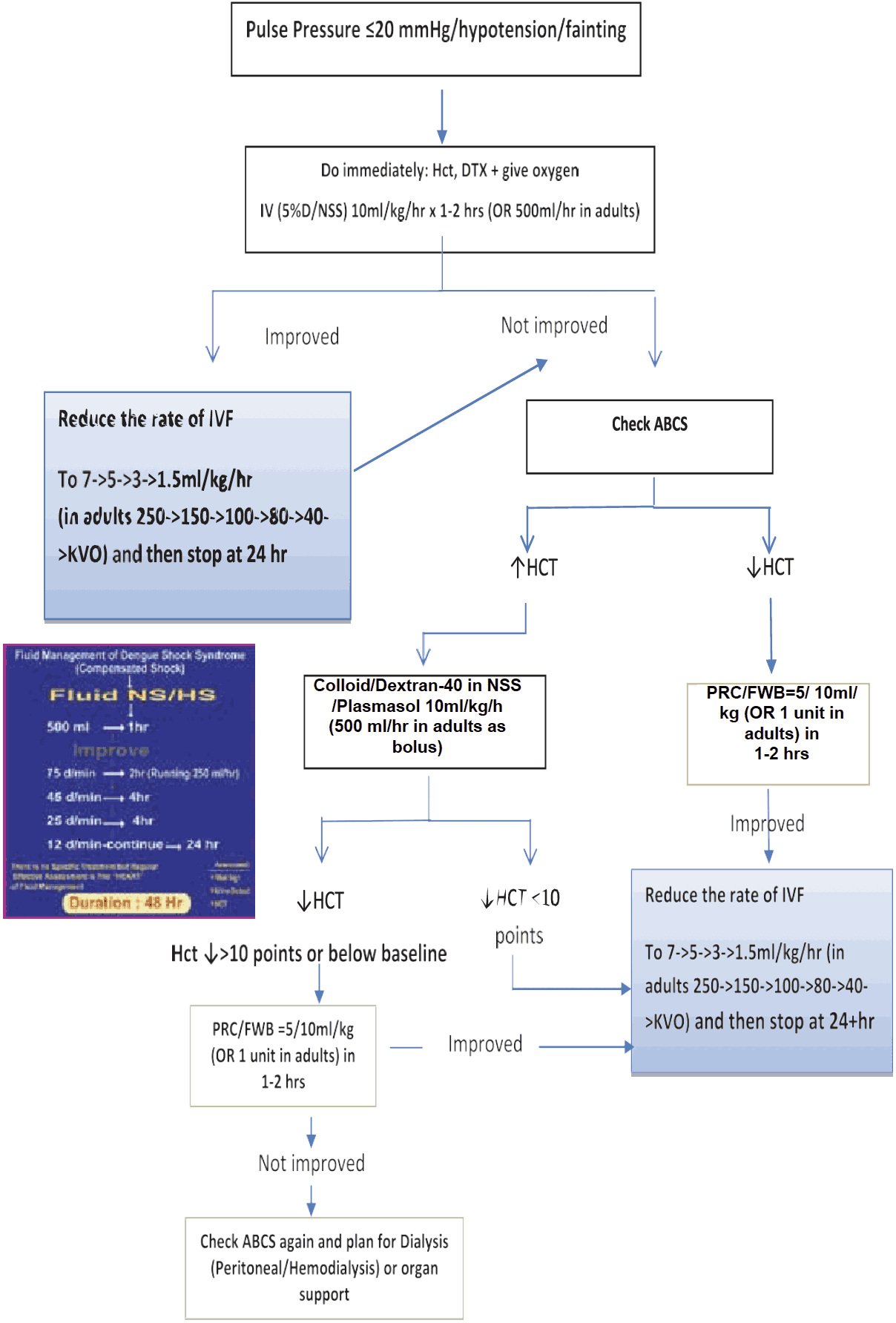

Figure 13 - Fluid Management for Dengue Shock

Figure 13 - Fluid Management for Dengue Shock

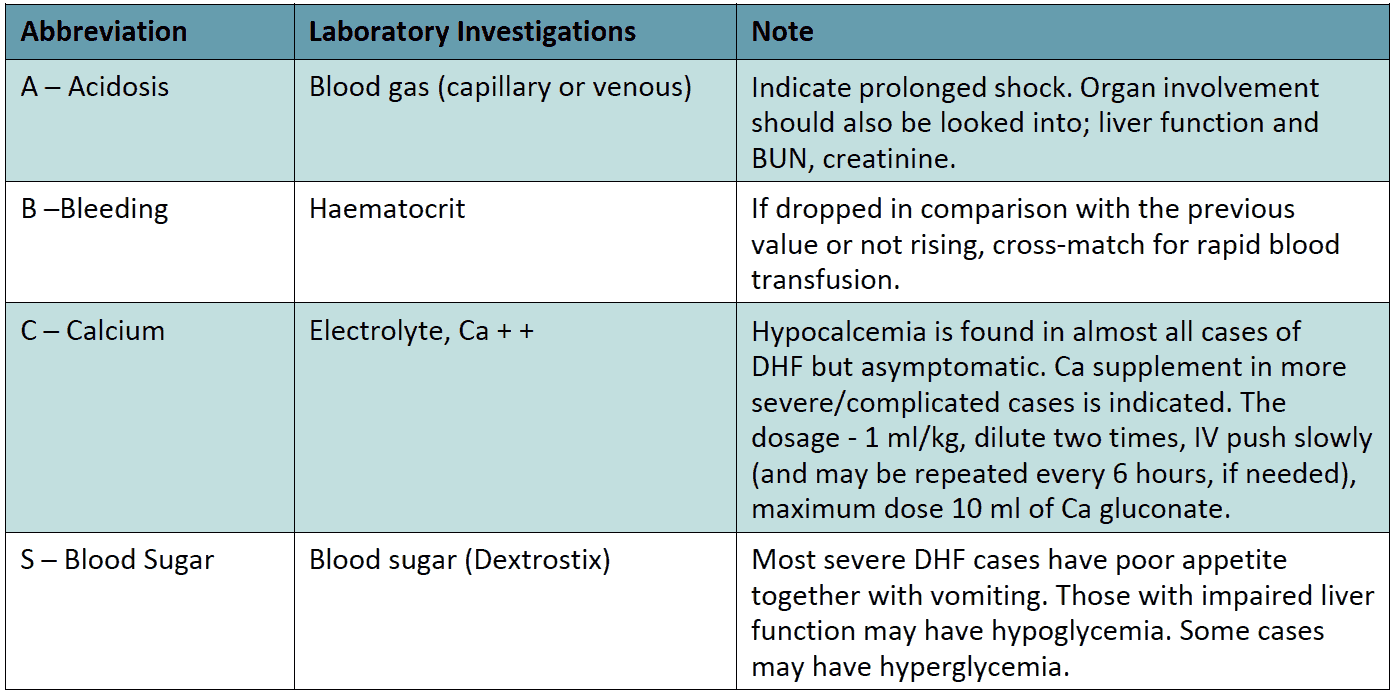

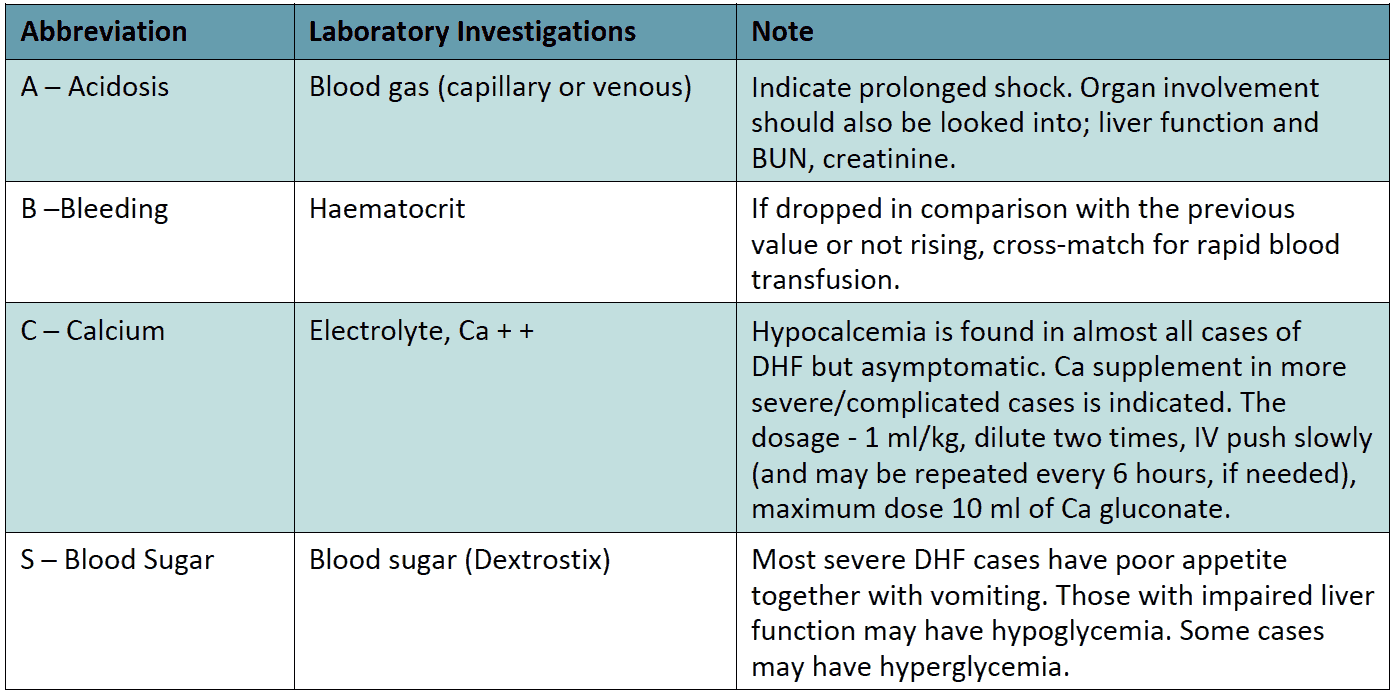

Laboratory investigations (ABCS) should be carried out in both shock and non-shock cases when no improvement is registered in spite of adequate volume replacement

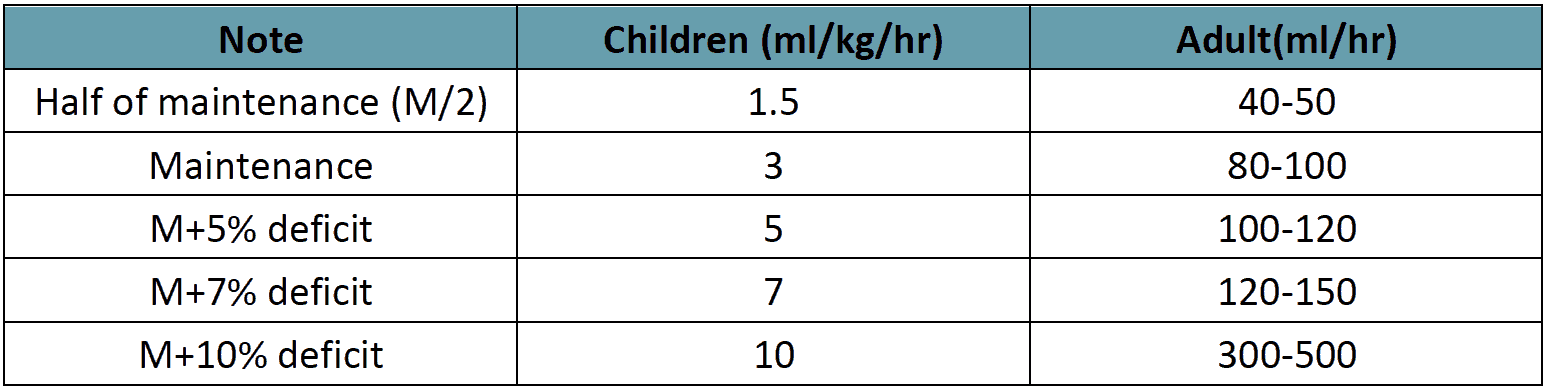

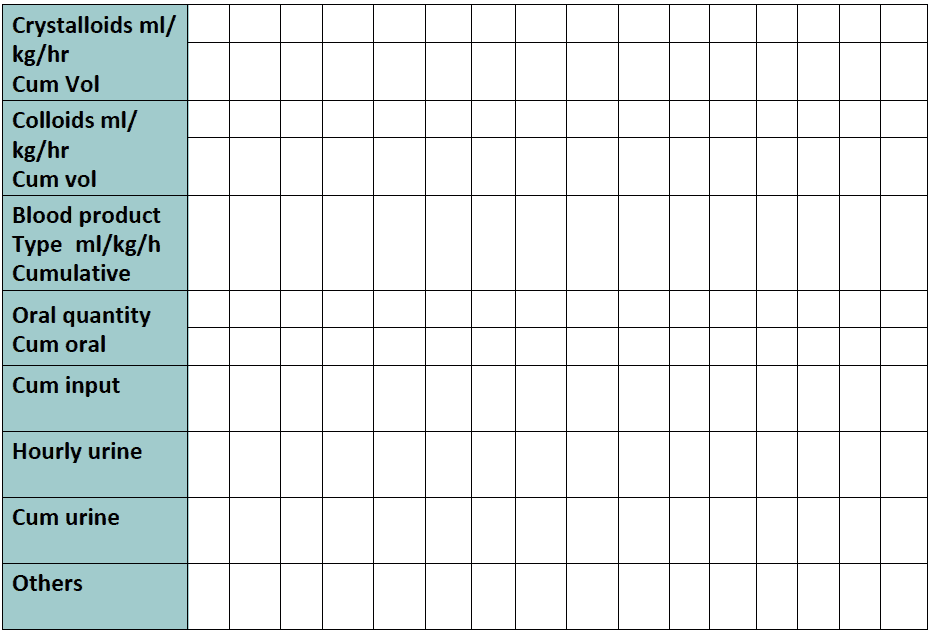

Table 13 - IV Fluid Therapy for Compensated shock

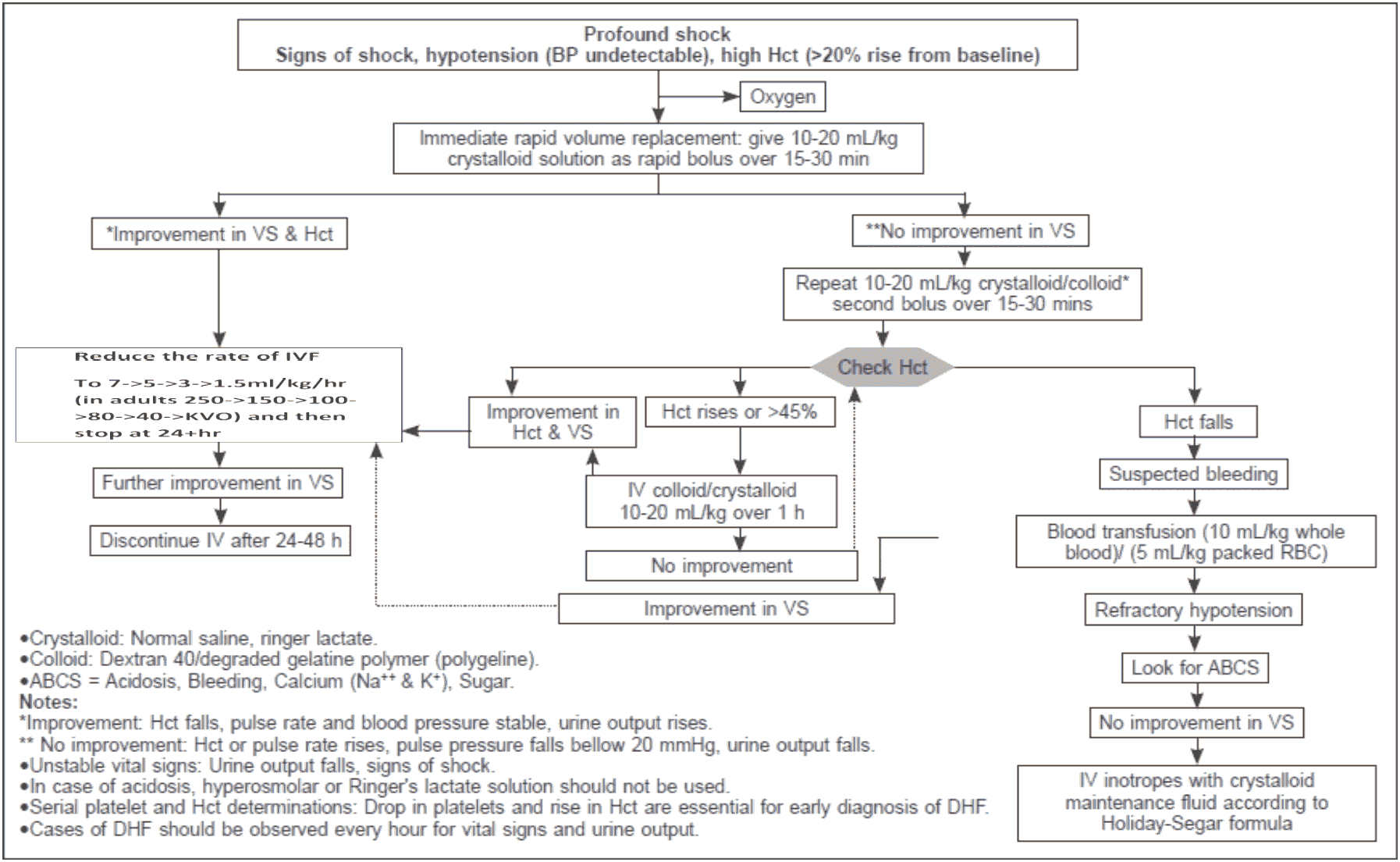

Decompensated shock (DSS, Profound hypotension)

- Preferably this group of patient need to manage in ICU setting.

- Oxygen should be started immediately.

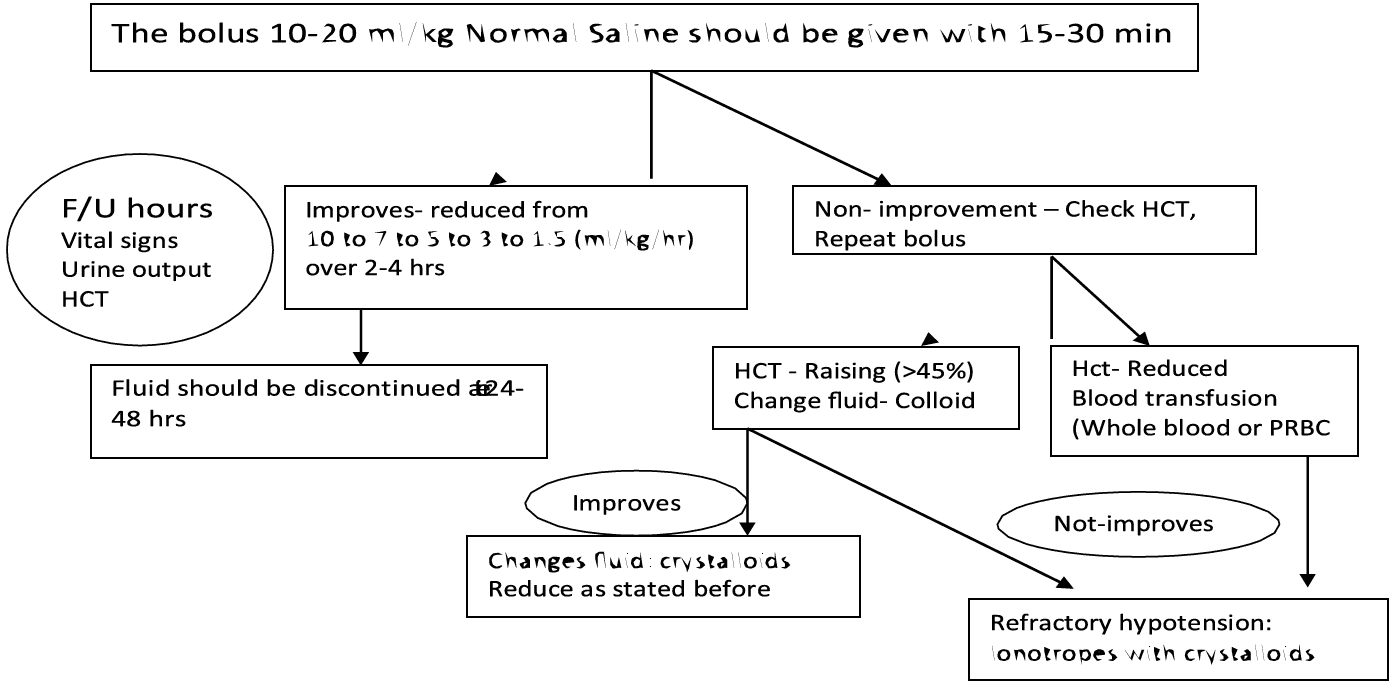

- The bolus 10-20 ml/kg crystalloids should be given within 15-30 min.

- If the vital signs and HcT improved, the fluid can be reduced from 10 ml/kg/hr to 6ml/kg/hr for 2 hours, then from 6 to 3 ml/kg/hr for 2-4 hrs and then 3 to 1.5 ml/kg/hr for another 2-4 hrs. Fluid should be discontinued after 24-48 hrs.

- If there is no clinical improvement after bolus crystalloids, check HcT. If the HcT is raising (more than 45%, then the fluid should be changed to colloid at (10- 20ml/kg/hr) and if there is improvement, then changes the fluid to crystalloids and successfully reduce as stated before. The highest dose of colloid will be 30 ml/kg/24 hour.

- If the initial bolus crystalloids fluid does not have improvement in vitals sign and HcT is reduced, then suspect concealed bleeding and blood transfusion should be started immediately at 10ml/kg whole blood or packed RBC at 5ml/kg.

- In case of refractory hypotension, look for ABCS and IV inotropes with crystalloids as per requirement is to be continued.

- In case of acidosis, hyperosmolar or ringers’ lactate should not be used.

- HcT measurement every hour is more important than platelet count during management.

Figure 14 - Volume Replacement Algorithm for Patient With DSS

Group C (Decompensate Shock) For Children

Example: In a child weighing 10 kg, the bolus fluid should be (10 x 10) = 100 ml over 30 min (50 drops/min). When patient becomes vitally stable, fluid should be continued @ 10 ml/kg/hr (10x10) = 100ml/ hr (25 drops/min). If improves, reduction should be done @ 7ml/kg/hr (7x10) = 70 ml/hr (18 drops/min), Then 5 ml/kg/hr (5x10) = 50 ml/hr (12 μdrops/min) and subsequently like this.

When to stop intravenous fluid therapy

- Cessation of plasma leakage;

- Stable BP, pulse and peripheral perfusion;

- Hematocrit decreases in the presence of a good pulse volume;

- Apyrexia (without the use of antipyretics) for more than 24–48 hours;

- Resolving bowel/abdominal symptoms;

- Improving urine output.

- Continuing intravenous fluid therapy beyond the 48 hours of the critical phase wil put the patient at risk of pulmonary oedema and other complications such as thrombophlebitis

Treatment of hemorrhagic complications

Patients at risk of severe bleeding are those who:

- Have profound/prolonged/refractory shock;

- Have hypotensive shock and multi-organ failure

- Have pre-existing peptic ulcer disease;

- Have any form of trauma, including intramuscular injection.

- Are given non-steroidal anti-inflammatory agents;

- Are on anticoagulant therapy;

Severe bleeding should be recognized in the following situations:

- Persistent and/or severe overt bleeding in the presence of unstable haemodynamic status, regardless of the haematocrit level;

- Decrease in haematocrit after bolus of fluid resuscitation unstable haemodynamic status;

- Refractory shock that fails to respond to consecutive fluid resuscitation of 40– 60 ml/kg;

- Hypotensive shock with inappropriately low/normal haematocrit;

- Persistent or worsening metabolic acidosis;

- Well-maintained systolic BP, especially in those with severe tenderness and distension.

The action plan for the treatment of hemorrhagic complications is as follows:

- If possible, attempts should be made to stop bleeding if the source of bleeding is identified e.g. severe epistaxis may be controlled by nasal adrenaline packing.

- Give aliquots of 5−10 ml/kg of fresh -packed red cells or 10−20 ml/kg of fresh whole blood (FWB) at an appropriate rate and observe the clinical response.

- It is important that fresh whole blood or fresh red cells are given.

- Oxygen inhalation-2-4 L/min

- Consider repeating the blood transfusion if there is further overt blood loss or no appropriate rise in haematocrit after blood transfusion in an unstable patient.

- There is no evidence that supports the practice of transfusing platelet concentrates and/or fresh-frozen plasma for severe bleeding in dengue.

- Transfusions of platelet concentrates and fresh frozen plasma in dengue were not able to sustain the platelet counts and coagulation profile. Instead, in the case of massive bleeding, they often exacerbate the fluid overload.

- In certain situations, such as obstetrical deliveries or other surgeries, transfusions of platelet concentrate with or without fresh blood should be considered in anticipation of severe bleeding.

- In gastrointestinal bleeding, H-2 antagonist and proton pump inhibitors have been used, but their efficacy have not been studied.

- Great care should be taken when inserting a nasogastric tube or bladder catheters which may cause severe hemorrhage. A lubricated orogastric tube may minimize the trauma during insertion. Insertion of central venous catheters should be done with ultra-sound guidance or by an experienced person.

- It is essential to remember that blood transfusion is only indicated in dengue patients with severe bleeding.

Glucose control

- Hyperglycaemia and hypoglycaemia may occur in the same patient at different times during the critical phase.

- Hyperglycaemia is associated with increased morbidity and mortality in critically ill adult and paediatric patients.

- Hypoglycaemia may cause seizures, mental confusion and unexplained tachycardia.

- Most cases of hyperglycaemia will resolve with appropriate (isotonic, non-glucose) and adequate fluid resuscitation.

- In infants and children, blood glucose should be monitored frequently during the critical phase and into the recovery phase if the oral intake is still reduced.

- However, if hyperglycemia is persistent, undiagnosed diabetes mellitus or impaired glucose tolerance should be considered and intravenous insulin therapy initiated.

- Hypoglycaemia should be treated as an emergency with 0.1−0.5g/kg of glucose, rather than with a glucose-containing resuscitation fluid.

- Frequent glucose monitoring should be carried out and euglycaemia should then be maintained with a fixed rate of glucose-isotonic solution and external feeding if possible.

Electrolyte and acid-base imbalances

- Hyponatraemia is a common observation in severe dengue

- The use of isotonic solutions for resuscitation will prevent and correct this condition.

- Hyperkalaemia is observed in association with severe metabolic acidosis or acute renal injury.

- Appropriate volume resuscitation will reverse the metabolic acidosis and the associated hyperkalaemia.

- Life-threatening hyperkalaemia, in the setting of acute renal failure should be managed with Resonium A and infusions of calcium gluconate and/or insulindextrose.

- Renal support therapy may have to be considered.

- Hypokalaemia is often associated with gastrointestinal fluid losses and the stressinduced hypercortisol state;

- It should be corrected with potassium supplements in the parenteral fluids.

- Serum calcium levels should be monitored and corrected when large quantities of blood have been transfused or if sodium bicarbonate has been used (Table 12)

Metabolic acidosis

- Compensated metabolic acidosis is an early sign of hypovolaemia and shock.

- Lactic acidosis due to tissue hypoxia and hypoperfusion is the most common cause of metabolic acidosis in dengue shock.

- Correction of shock and adequate fluid replacement will correct the metabolic acidosis.

- If metabolic acidosis remains uncorrected by this strategy, one should suspect severe bleeding and check the haematocrit. Transfuse fresh whole blood or fresh packed red cells urgently.

- Sodium bicarbonate for metabolic acidosis caused by tissue hypoxia is not recommended for pH ≥ 7.10. Bicarbonate therapy is associated with sodium and fluid overload, an increase in lactate and pCO2 and a decrease in serum ionized calcium. A left shift in the oxy–haemoglobin dissociation curve may aggravate the tissue hypoxia.

- Hyperchloraemia, caused by the administration of large volumes of 0.9% sodium chloride solution (chloride concentration of 154 mmol/L), may cause metabolic acidosis with normal lactate levels.

- If serum chloride levels increase, use Hartmann’s solution or Ringer’s lactate as crystalloid. These do not increase the lactic acidosis

Signs of recovery:

• Stable pulse, blood pressure and breathing rate.

• Normal temperature.

• No evidence of external or internal bleeding.

• Return of appetite.

• No vomiting, no abdominal pain.

• Good urinary output.

• Stable hematocrit at baseline level.

• Convalescent confluent petechiae rash or itching, especially on the extremities.

Discharge Criteria:

• No fever for at least 24 hours without the usage of antipyretic drugs

• At least two days have lapsed atier recovery from shock

• Good general condition with improving appetite

• Normal HcT at baseline value or around 38 - 40 % when baseline value is not known

• No distress from pleural effusions

• No ascites

• Platelet count has risen above 50,000 /mm3

• No other complications

Fluid Overloaded Patient:

Some degree of fluid overload is inevitable in patients with severe plasma leakage. The skill is in giving them just enough intravenous fluid to maintain adequate perfusion and at the same time avoiding excessive fluid overload.

Causes of excessive fluid overload:

- Excessive and/or too rapid intravenous fluids during the critical phase.

- Incorrect use of hypotonic crystalloid solutions e.g. 0.45% sodium chloride solutions.

- Inappropriate use of large volumes of intravenous fluids in patients with unrecognized severe bleeding.

- Inappropriate transfusion of fresh-frozen plasma, platelet concentrates and cryoprecipitates.

- Prolonged intravenous fluid therapy, i.e., continuation of intravenous fluids after plasma leakage has resolved (> 48 hours from the start of plasma leakage)

- Co-morbid conditions such as congenital or ischaemic heart disease, heart failure, chronic lung and renal diseases.

Clinical features of fluid overload:

- Rapid breathing

- Suprasternal in-drawing and intercostal recession (in children)

- Respiratory distress, difficulty in breathing

- Wheeze, crepitations

- Large pleural effusions tense ascites, persistent abdominal discomfort/pain/tenderness (this should not be interpreted as warning signs of shock)

- Increased jugular venous pressure (JVP)

- Pulmonary oedema (cough with pink or frothy sputum, wheezing and crepitations, cyanosis) - this may be mistaken as pulmonary hemorrhage

- Irreversible shock (heart failure, often in combination with ongoing hypovolaemia)

- Puffy Face & leg oedema

Additional investigations needed:

- Blood gas and lactate analysis

- Chest X-ray which shows cardiomegaly, pleural effusion, features of heart failure

- ECG to exclude ischaemic changes and arrhythmia

- Echocardiogram for assessment of left ventricular function

- Cardiac enzymes

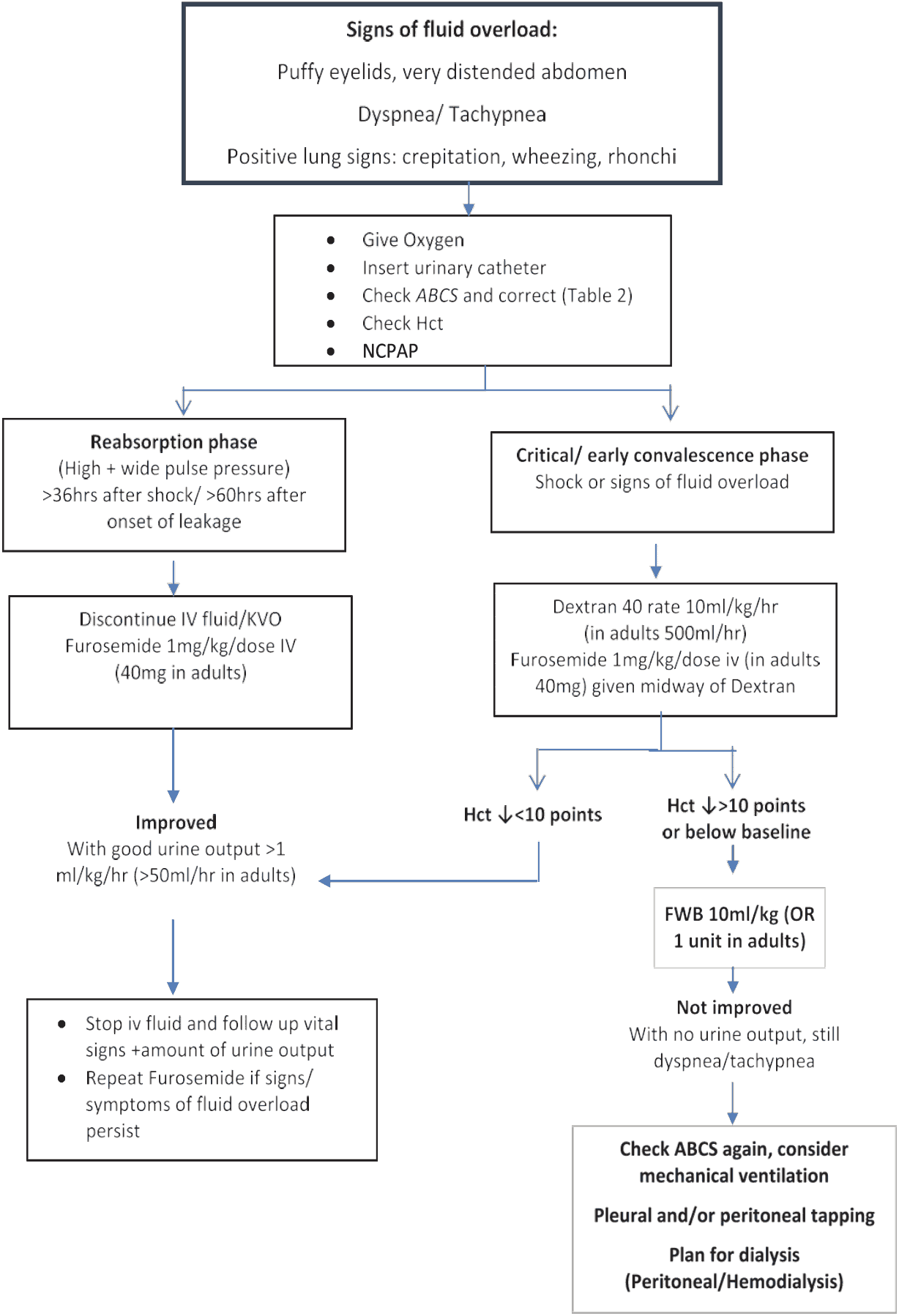

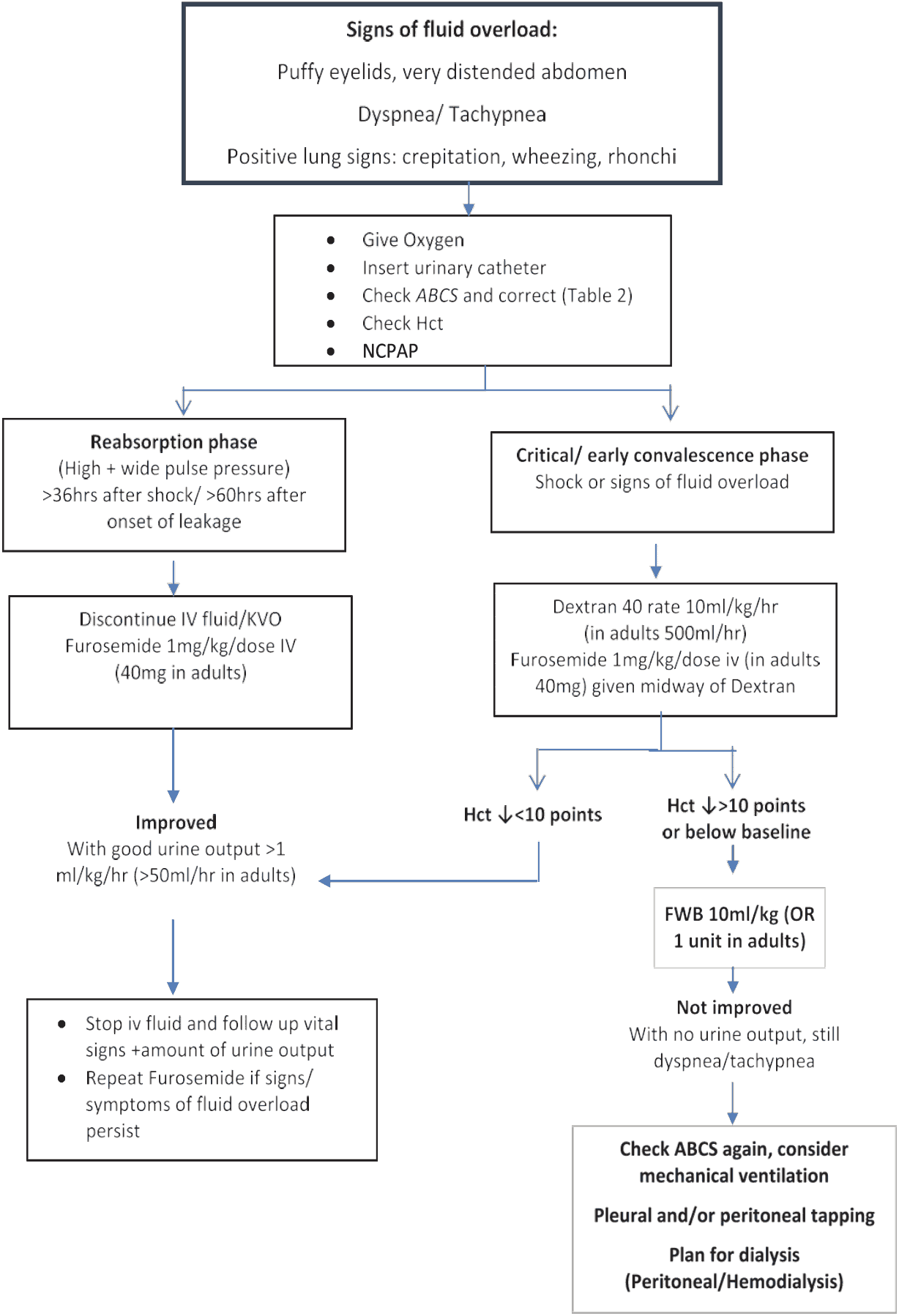

Management of fluid overload:

- Review the total intravenous fluid therapy and clinical course & check and correct for ABCS.

- All hypotonic solutions should be stopped.

- Switch from crystalloid to colloid solutions as bolus fluids.

- Dextran 40 is effective as 10 ml/kg bolus infusions, but the dose is restricted to 30 ml/kg/day because of its renal effects.

In the late stage:

- Intravenous Furosemide may be administered if the patient has stable vital signs.

- If the patient is in shock, together with fluid overload 10 ml/kg/hr of colloid (dextran) should be given.

- When the blood pressure is stable, usually within 10 to 30 minutes of administer IV 1 mg/kg/dose of furosemide and continue with infusion, dextran infusion until completion.

- Intravenous fluid should be reduced to as low as 1 ml/kg/hr until when haematocrit decreases to baseline or below (with clinical improvement).

Figure 15 - Flow diagram for the Management of Fluid Overload

The following points should be noted:

- These patients should have a urinary bladder catheter to monitor hourly urine output

- Intravenous Furosemide should be administered during dextran infusion because the hyperoncotic nature of dextran will maintain the intra vascular volume while furosemide depletes in the intravascular compartment. After administration of furosemide, the vital signs should be monitored every 15 minutes for one hour to note its effects.

- If there is no urine output in response to furosemide, check the intravascular volume status (CVP or lactate). If this is adequate, pre-renal failure is excluded, implying that the patient is in an acute kidney injury state. These patients may require ventilator support soon. If the intravascular volume is inadequate or the blood pressure is unstable, check the ABCS and other electrolyte imbalances

- In cases with no response to furosemide (no urine obtained), repeated doses of furosemide and doubling of the dose are recommended. If oliguric renal failure is established, renal replacement therapy is to be done as soon as possible. These cases have poor prognosis.

- Pleural and/or abdominal tapping may be indicated and can be life-saving in cases with severe respiratory distress and failure of the above management. This has to be done with extreme caution because traumatic bleeding is the most serious complication and can be detrimental. Discussions and explanations about the complications and the prognosis with families are mandatory before performing this procedure.

Management of encephalopathy:

- Some DF/DHF patients present unusual manifestations with signs and symptoms of central nervous system (CNS) involvement, such as convulsion and/or coma. This has generally been shown to be encephalopathy, not encephalitis, which may be a result of intracranial hemorrhage or occlusion associated with DIC or hyponatremia.

- Most of the patients with encephalopathy are reported to have hepatic encephalopathy. The principal treatment of encephalopathy is to prevent the increase of intracranial pressure (ICP). Radiological imaging of the brain (CT scan or MRI) is recommended if available to rule out intracranial hemorrhage.

Recommendations for supportive therapy for this condition:

- Maintain adequate airway oxygenation with oxygen therapy.

- ICP by the following measures:

- Give minimal IV fluid to maintain adequate intravascular volume; ideally the total IV fluid should not be >80% fluid maintenance.

- Switch to colloidal solution earlier if haematocrit continues to rise and a large volume of IV is needed in cases with severe plasma leakage.

- Administer a diuretic if indicated in cases with signs and symptoms of fluid overload.

- positioning of the patient must be with the head up by 30 degrees.

- early intubation to avoid hypercarbia and to protect the airway.

- may consider steroid to reduce ICP. Dexamethasone 0.15 mg/kg/dose IV to be administered every 6–8 hours.

- Decrease ammonia production by giving lactulose 5–10 ml every six hours for induction of osmotic diarrhoea. local antibiotic gets rid of bowel flora; it is not necessary if systemic antibiotics are given.

- Maintain blood sugar level at 80–100 mg/dl per cent. Recommend glucose infusion rate is anywhere between 4–6 mg/kg/hour.

- Correct acid-base and electrolyte imbalance, e.g. correct hypo/hypernatremia, hypo/ hyperkalemia, hypocalcemia and acidosis. Vitamin K1 IV administration; 3 mg for <1-year-old, 5 mg for <5-year old and 10 mg for>5-year-old and adult patients.

- Anticonvulsants should be given for control of seizures: phenobarbital, dilantin and diazepam IV as indicated.

- Transfuse blood, preferably freshly packed red cells, as indicated. Other blood components such as platelets and fresh frozen plasma may not be given because the fluid overload may cause increased ICP.

- Empiric antibiotic therapy may be indicated if there are suspected superimposed bacterial infections.

- H2-blockers or proton pump inhibitor may be given to alleviate gastrointestinal bleeding.

- Consider plasmapheresis or haemodialysis or renal replacement therapy in cases with clinical deterioration.

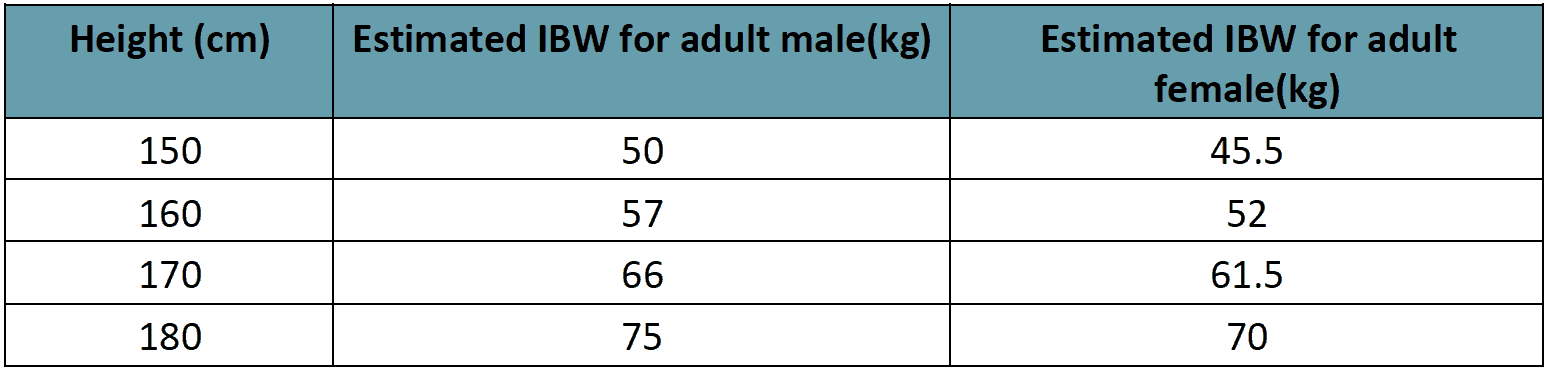

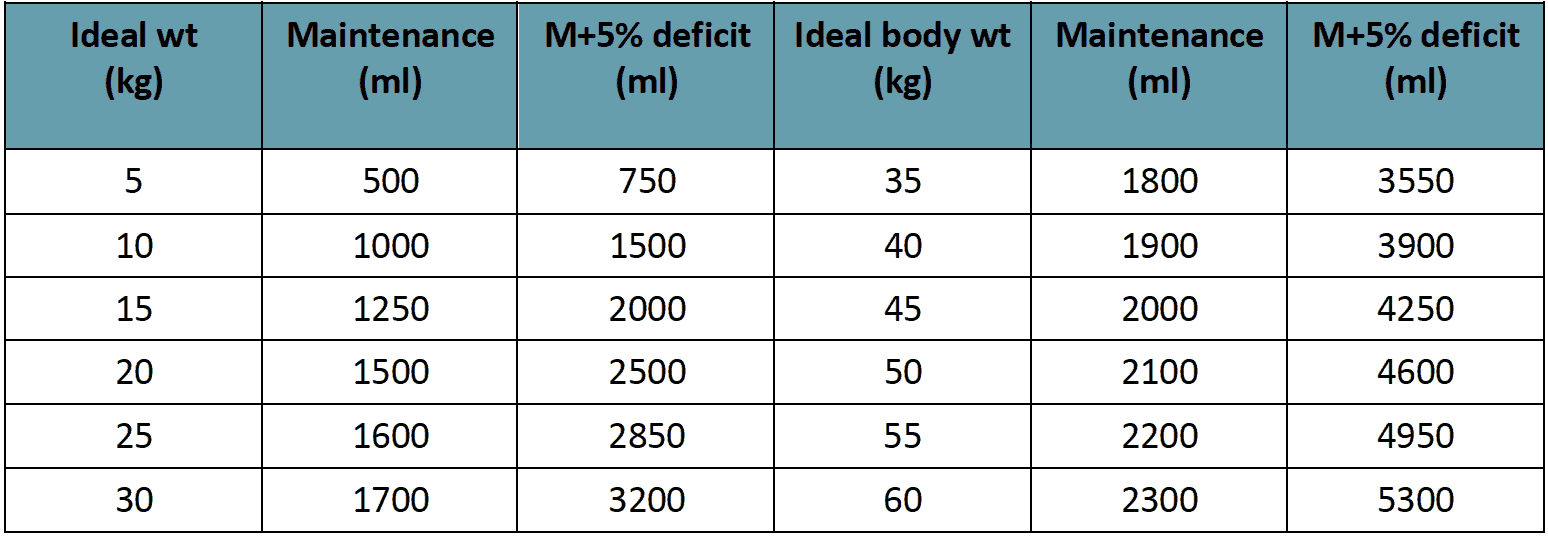

Rate of IV fluid for children (Rate for adults)

Rate of IV fluid for children (Rate for adults)

Figure 13 - Fluid Management for Dengue Shock

Figure 13 - Fluid Management for Dengue Shock