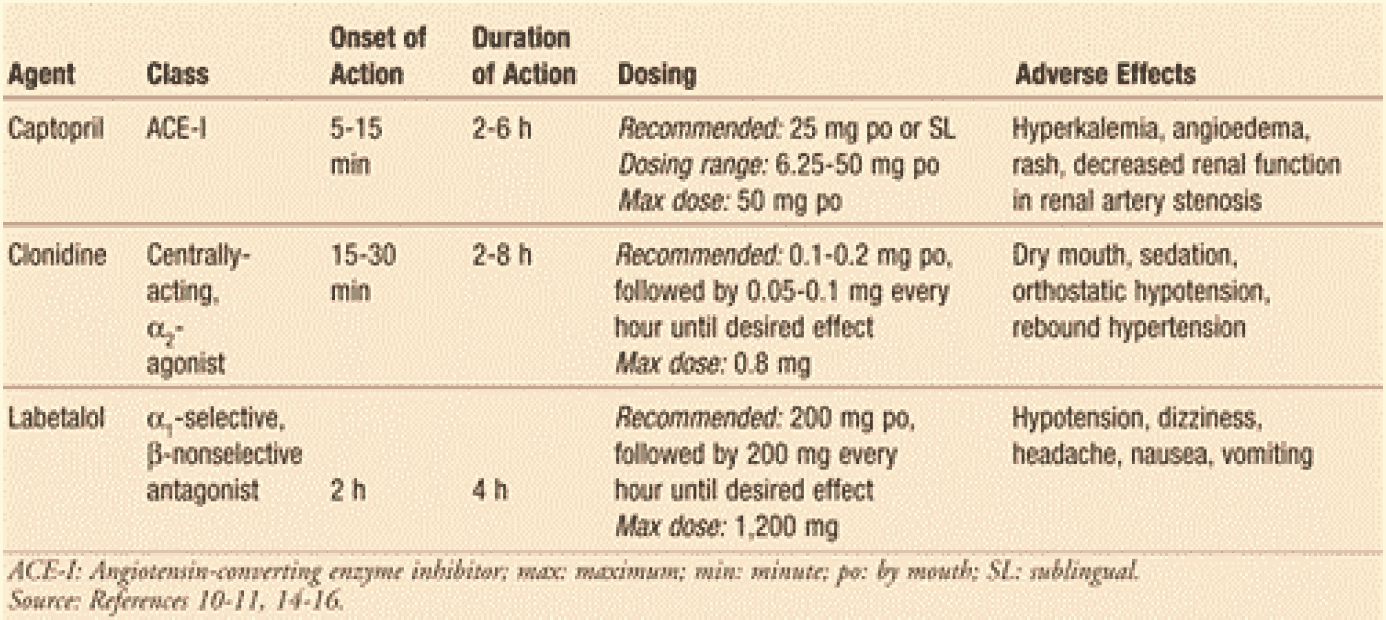

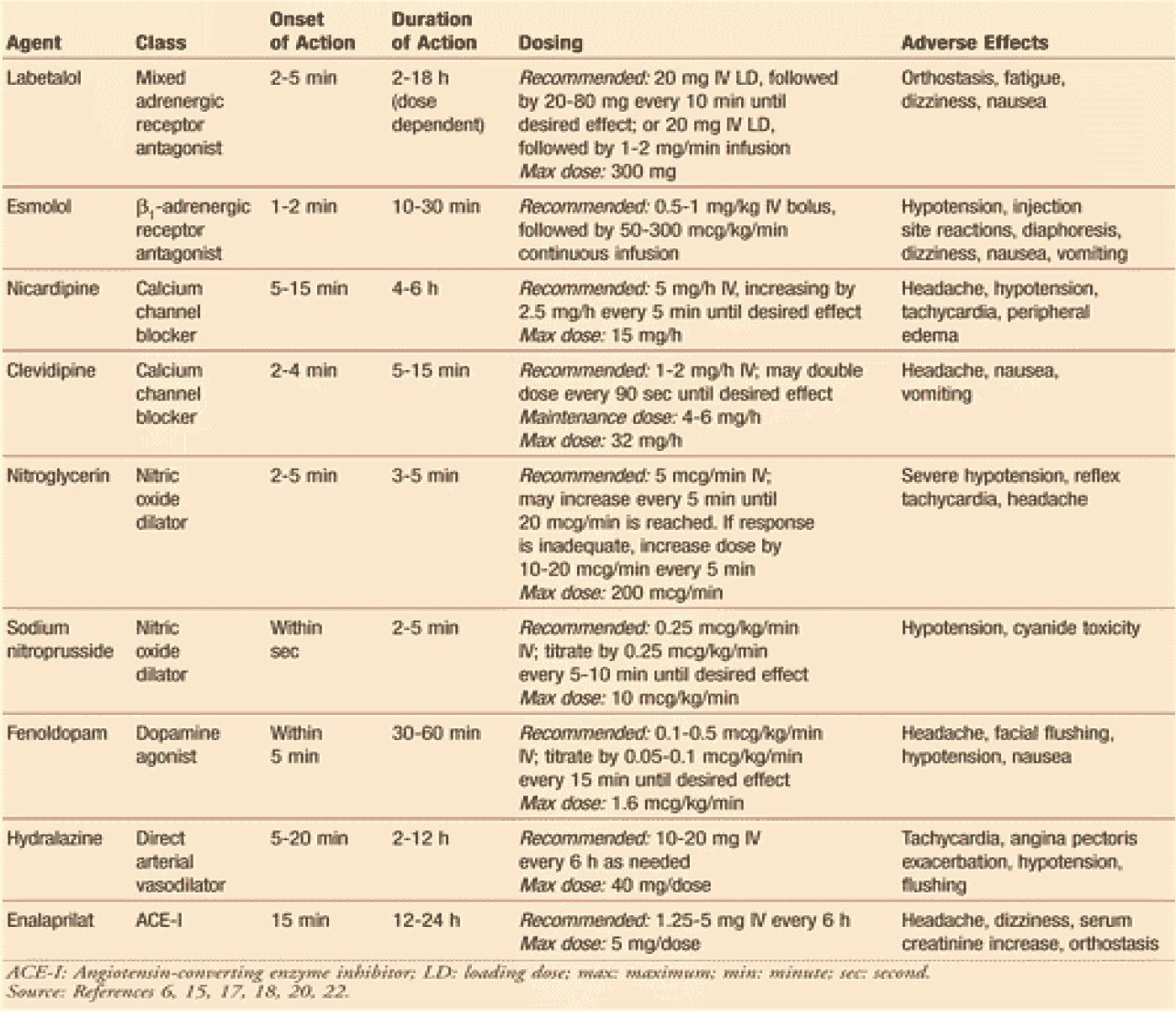

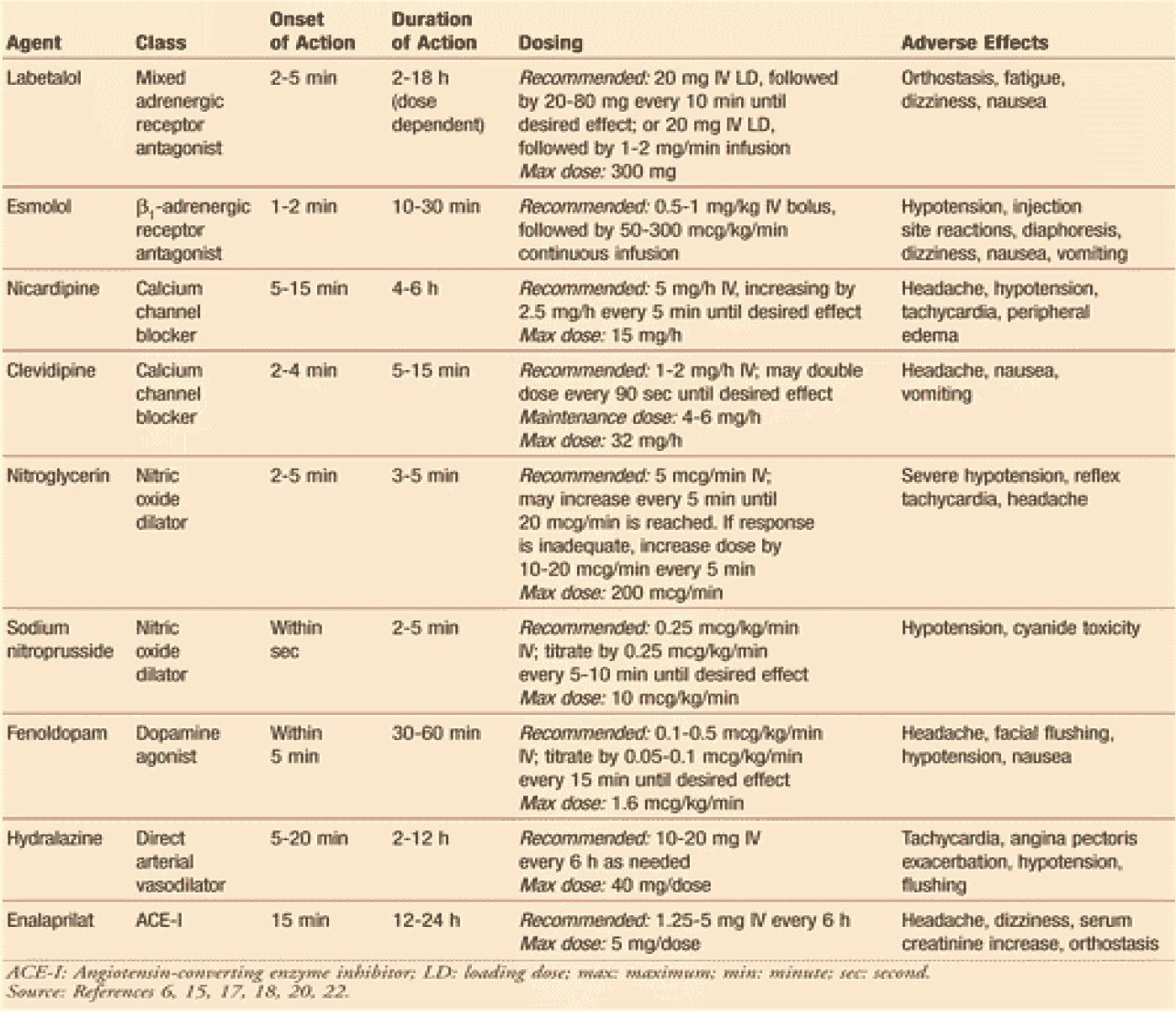

Hypertensive emergencies require immediate medical attention, including admission to the intensive care unit. Continuous cardiac monitoring, frequent measurement of urine output, and neurologic assessment are all necessary. Treatment with IV antihypertensive agents (TABLE 8) is warranted in this setting. Drug selection should be based on specific characteristics of the drug (i.e., adverse effects) and patient-specific attributes, such as volume status and the presence of comorbidities16.

Table 8: Treatment options for hypertensive emergencies.

The primary goal would be to lower the mean arterial pressure by no more than 25% within the first hour, followed by BP reduction to 160/110-100 mmHg within the next 2 to 6 hours1.

BP reduction must be conducted in a controlled fashion in order to prevent organ hypoperfusion and subsequent ischemia or infarction3. However, in patients with aortic dissection, BP must be aggressively lowered3. Once the BP has stabilized and the risk of end-organ damage has dissipated, downward titration of the IV agent may begin, followed by conversion to oral therapy. The clinician should then attempt to ascertain causative factors for the event.